I/ Introduction to Barraquismo

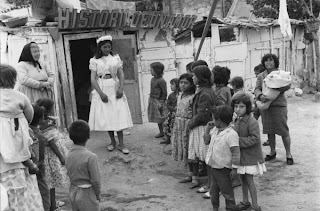

In the beginning of the XXth century in Barcelona, a new

urban phenomenon appeared with the arrival of immigrants from other

Spanish regions. The city, facing a crisis of dwelling, was already

lacking a sufficient number of housing and without any specific type

of plan people started to make their housing in the already existing

neighborhood such as el Somorrostro, Pequín i el Camp de la Bota,

the littoral, Tres Pins i Can Valero, Montjuïc... These urban nuclei

became more and more popular and were the beginning of an intensive

urbanization that led to shantytowns and constructive anarchy

especially reinforced during the post-war period.

**Interview of people that arrived in Barcelona and lived in

barracas or witnessed the process of urbanization.**

|

| Overview barraquismo © 2008

MUHBA

www.museuhistoria.bcn.cat |

2/ Landscape of

the shantytowns

Typologies of shanties: construction methods,

materials and dimensions

The shanties of the

various nuclei belonged to diverse typologies which were adapted to

the pre-existing paths, to the lay of the land and to the internal

organization of each shantytown as a whole. On the hills of the city

there were shantytowns with a certain air of the southern

Mediterranean, while by the sea they had a more maritime appearance

and even included some stilt houses.

Shanties were erected on

land which was purchased or assigned or was public property. Some

were built of quite solid load-bearing materials: bricks and

baked-clay roof tiles, while others were more precarious, with waste

or recycled material: wood, cardboard and fibre-cement panels. The

dimensions were minimal and varied according to the services and

equipment of the home: kitchens, latrines, wash-house. The interior

space was often divided into two areas: one for living in general and

the other for sleeping, separated by curtains. With the passing of

time, the shanties and the shantytowns improved both their

constructed condition and equipment, with the incorporation of

electrical devices and home appliances.

THE SHANTY: A MICROCOSM

OVERLOOKING THE STREET © 2008

MUHBA

www.museuhistoria.bcn.cat

3/ Documentary TV3

Barraques- La

ciutat oblidada 1.51 min

Un reportatge de:

Alonso

Carnicer

i Sara

GrimalMuntatge:

Agustí

PochDocumentació:

Miracle

Tous

.jpg)